Consequences of Removal

In the beginning of the twentieth century, San Diego County experienced significant growth in its population. In order to support the influx of new people the county needed to increase its supply of fresh water for irrigation. The creation of a reservoir to support the county was the obvious solution. The only argument became where to place this new man made lake.

Two sites within the county were geographically suited to support the construction of a large reservoir. The first was in Mission Gorge and the second was a valley in Capitan Grande. The architect for the project, Hiram Savage, preferred the Mission Gorge location as it was closer to the city and the rocky, deep canyon walls would reduce the amount of water lost to evaporation. The city on the other hand, preferred the valley in Capitan Grande as the flooding of Mission Gorge would also flood sections of Mission Valley. At the time Mission Valley was an agriculturally productive area for the city and flooding it would have severe economic repercussions. Despite Savage’s continued objections, the city decided to build the reservoir in the Capitan Grande valley. The valley after all had no agricultural value to San Diego as it was part of an Indian reservation.

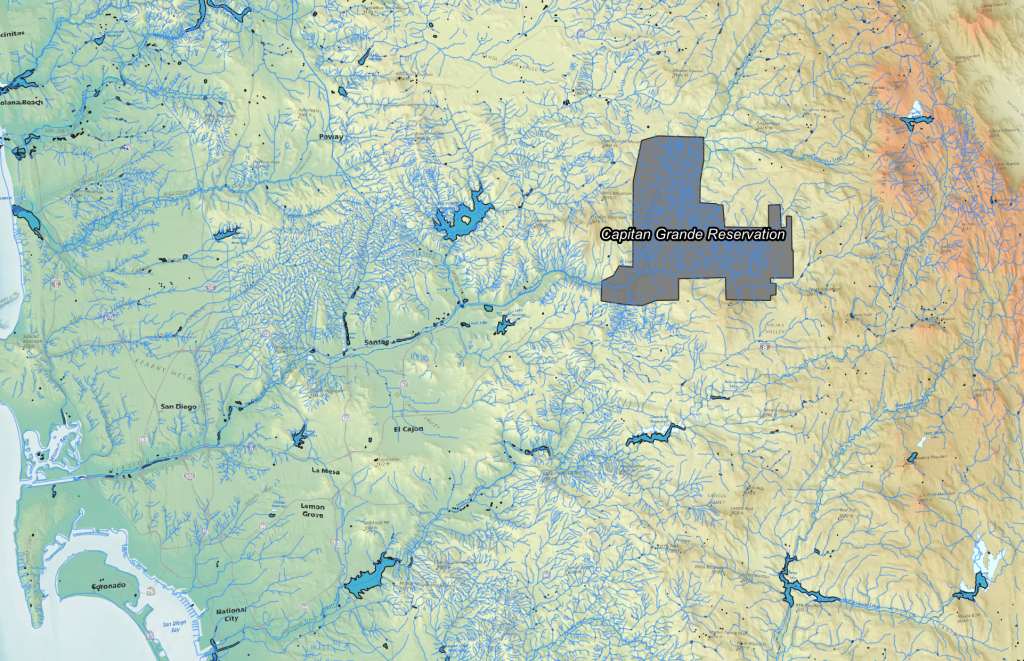

The Capitan Grande Reservation was created in 1875 by executive order. The San Diego River ran through the heart of the reservation and provided adequate irrigation for the Kumeyaay and Conejos tribes to run productive farms. In the early twentieth century, agriculture was the primary method of making a living for the Kumeyaay. According to the 1910 census, 46% of Kumeyaay men had agricultural occupations. The proposed San Diego County reservoir would flood this productive farmland and force the Kumeyaay and Conejos from their homes. Because of the objections from tribal leadership to the proposed reservoir, San Diego County was forced to appeal to Congress to obtain the water rights for the reservation.

In 1919 Congress passed the ‘El Capitan’ act which allowed San Diego to purchase the water rights for the Capitan Grande valley as well as the surrounding acreage for $361,420.00. The purchase carved out the heart of the Capitan Grande Reservation and cut the Kumeyaay off from their main source of flowing groundwater. An additional expansion to the ‘El Capitan’ act in 1932 provided San Diego with the authority to force all of the Kumeyaay to vacate the reservation regardless of their proximity to the flood zone.

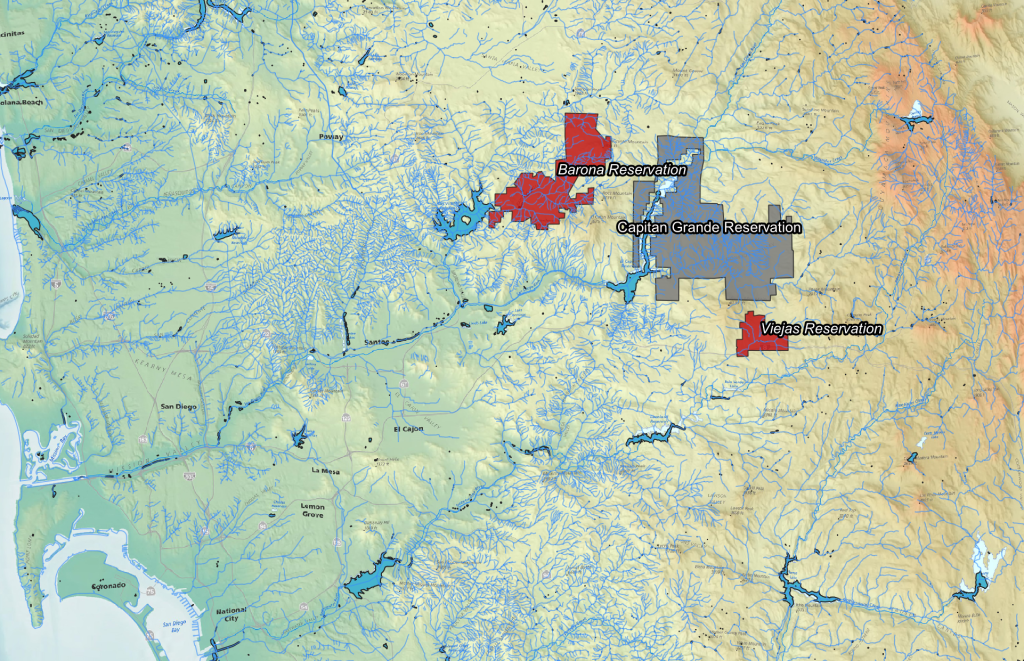

Despite this devastating blow, the Kumeyaay and Conejos tribes fought the U.S. government in court and secured additional land rights. For the Kumeyaay, the lengthy legal struggle resulted in the creation of the Barona and Viejas Reservations. While this monumental legal victory helped to shape the political atmosphere surrounding forced relocation, the land set aside for the Barona and Viejas Reservations was poorly suited for agriculture.

Unlike the Capitan Grande Reservation, Barona and Viejas had almost no access to groundwater and the Kumeyaay farmers were forced to rely on scant rainfall to support their farms. By the 1930s the inability to produce enough crop to sustain a living forced almost half of the Kumeyaay off of Barona and Viejas Reservations in search of new occupations.

Below is an animated map that shows the reduction in size of the Capitan Grande Reservation as well as the establishment of the Barona and Viejas Reservations.