Landscape designers for San Diego’s City Park sought to create pastoral-like nature for people to enjoy away from the city life. Much of the historiography about park history, including that of Balboa Park, focuses on the two big ideas of picturesque and city beautiful shaping the way landscape designers created nature in parks. While the picturesque and City Beautiful movements were leading park designs, there are other ideas about nature going on that are influencing the way designers created nature in parks. This thesis digital project acknowledges the various ideas landscape designers of City Park, later Balboa Park, had about nature that shaped the way the park was designed.

Philanthropists Ephraim M. Morse and George Marston were instrumental early on in securing the land early on in securing the land for the park. Morse originally proposed to utilize the fourteen-hundred acre lot of pueblo lands to create a park, and Marston was eager to hire a landscape architect to begin designing the park. Marston’s daughter, Mary Gilman Marston, was a teenager at the time of the early park planning. Hired by her father to work as a secretary behind the scenes of San Diego’s City Park construction, Marston documented the events and people involved, and later wrote about it in a memoir about her father. [3]

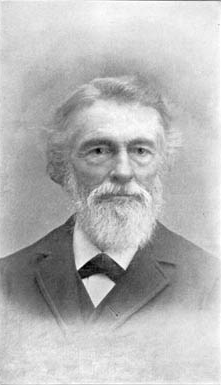

George White Marston (1850-1946)

George White Marston was a store owner and entrepreneur in San Diego during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When the San Diego City Council first discussed transforming a fourteen-hundred acre plot of pueblo lands into a City Park, Marston volunteered to pay for the hire of a landscape architect. ‘In 1902, Marston put up $10,000 so the Park Commission could hire Samuel Parsons Jr., to prepare the first comprehensive plan for Balboa Park.’[5] In 1908 he contributed to the hiring of landscape architect John Nolen. Marston valued the park throughout his life, and he remained an active philanthropist in San Diego throughout his life.

Mary Gilman Marston (1879-1987)

Mary Gilman Marston is the daughter of George White Marston. When she was a teenager, she began working as a secretary for park planning in San Diego’s City Park. She documented the people and events happening in the park during the early years, including her fathers relationship to the park and many of the landscape designers over time. In 1956 Marston published a memoir: George White Marston, A Family Chronicle v. 1 & 2, that included stories of her fathers life, family history, and documentation of the early years in Balboa Park. In the book, Marston acknowledges that Ephraim M. Morse was instrumental in securing the fourteen-hundred acres of Pueblo lands in what would become Balboa Park. [3] Her documentation provides a close interpretation of what was going on behind the scenes with pioneering landscape designers in the park.

Mary B. Coulston (1855-1904)

Mary B. Coulston was a key person involved in the early planning of City Park. Her experience as previous editor for Garden and Forest magazine in New York allowed her to become personally connected to many of the pioneering landscape designers. George Marston hired Coulston to advertise the park in newspaper publications. Her expertise was also sought in securing the first landscape architect for the park, Samuel Parsons Jr. Coulston’s publications in the San Diego Union and San Diego Daily Bee were influential in attracting people to San Diego’s City Park and promoting nature in the park during the early days of park planning. From the time Coulston moved to San Diego, she was an active citizen and remained involved in many social organizations. In 1904, Coulston passed away suddenly from a medical emergency. Kate Sessions memorialized her dear friend in the park with a bed of flowers. [1]

Kate O. Sessions (1857-1940)

Kate O. Sessions is the “Mother of Balboa Park.” Sessions was a horticulturalist born in Northern California, who studied tree and plant life with a scientific lens from an early age. She documented nature by drawing the things she saw, and writing various notes over the years. Sessions valued nature and beautifying the city of San Diego including Balboa Park with trees, flowers, and plants from around the world that were adaptable to the climate of Southern California. Her vision as a designer of nature in San Diego was more on the exotic side, with a goal of creating a subtropical paradise. Today, Sessions is memorialized with a statue in Balboa Park, an elementary school named after her, and many books authored about her life. She was instrumental in designing nature in the park, and many of the trees she planted remain growing throughout San Diego. [4]

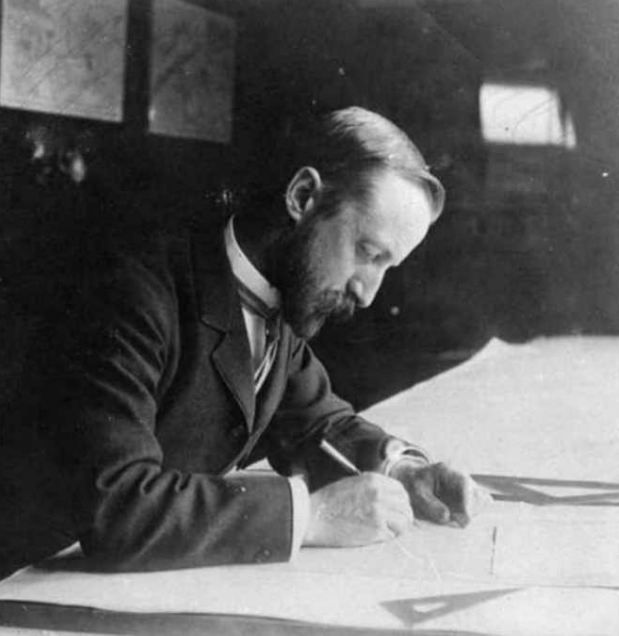

Samuel Parsons Jr. (1844-1923)

Samuel Parsons Jr. was a pioneering landscape architect from New York. Prior to his involvement as a planner for City Park in San Diego, Parsons partnered with leading architect Calvert Vaux on several projects such as the Washington Square park in 1871. He was a regular contributor to New York’s Garden and Forest magazine, where Coulston was an assistant editor. Coulston was the one to convince Parsons that San Diego was worthy of designing. He had a vision for creating a picturesque view with roads that contoured to the mesas. Parsons’ contributions to San Diego’s City Park are remembered, and remnants of his pastoral design are present in areas of Balboa Park. [1]

George Cooke (1849-1908)

George Cooke was a self trained landscape and city planner. Cooke specialized in designing roadways throughout cities and parks. Parsons and Cooke met in New York during the pioneering years of landscape design. They became partners and later worked together during the early years of San Diego’s City Park planning. With Parsons’ vision of maintaining the natural layout of the landscape, Cooke designed the roadways to curve around the canyons. He planned to have trees planted along the roadways to keep nature in the park secluded. Together Parsons and Cooke worked to transform the Pueblo landscape in City Park, creating a pastoral version of nature for people in the city to enjoy. Like Coulston, Cook passed tragically due to injuries he suffered from a horse carriage accident. He was dedicated to helping transform the City of San Diego and City Park with the planning of roadways connecting people in the city to nature. [1]

John C. Olmsted (1852-1920) and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (1870-1957)

John C. Olmsted followed in his fathers footsteps, entering into the field of pioneering landscape architecture at an early age. Similarly his younger brother, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., followed the path of their father as a pioneering landscape architect, city planner, and wildlife preservationist. After their father’s retirement, the brothers inherited his firm and renamed it Olmsted Brothers in 1898. They were involved in park planning in cities across the country including Boston, Atlanta, Detroit, Buffalo, and Chicago among others.

In 1908 the Olmsted Brothers were hired to assist in designing San Diego’s City Park for the Panama-California exposition. The Olmsted brothers valued secluded pastoral nature in parks away from the city life, as preached by their father. When other designers involved in planning the exhibition submitted a plan separate from the Olmsted Brothers plan that involved adding more buildings in the open mesas of the park, the brothers resigned their services claiming they would not be a part of ruining nature in the park. While they did not remain involved in Balboa Park exposition planning, the brothers’ contribution to landscape architecture and involvement in the park remain valuable to the history of San Diego. [6]

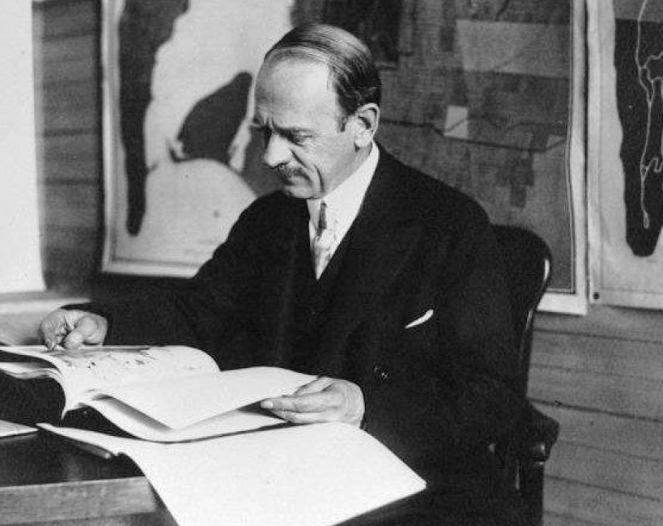

John Nolen (1869-1937)

John Nolen was a pioneering city planner during the City Beautiful Movement. He planned state park systems and redesigned cities throughout the country in places such as Madison, Wisconsin and San Diego, California. While Nolen was involved in the City Beautiful movement, he carried the admiration of picturesque pastoral in city parks held by pioneering architects. In his 1908 plan, Nolen “criticized the destruction of San Diego’s natural topography.”[2] He pointed out that “the leveling of hills and mesas removed some of the city’s most unique attributes” and it was a “destruction of a rare opportunity to secure significant beauty.”[2] Nolen’s designs for Balboa Park and the City of San Diego were instrumental in connecting the city to nature and the park to the city. He helped plan the beautification of buildings, streets, and parks. Nolen’s love for preservations of nature remains evident in his plans to incorporate systems of state parks and documented interviews.

Conclusion

During the early stages of planning for San Diego’s City Park, local horticulturalist Kate Sessions, known as the Mother of Balboa Park, called upon her friend Mary B. Coulston to help initiate the beginning plans for the park. Previously an assistant editor for Garden and Forest Magazine in New York, Coulston personally knew many pioneering landscape architects, botanists, and horticulturalists. Shortly after Coulston was approached by Marston for advice in hiring a landscape designer, Samuel Parsons Jr. and his partner George Cooke became the first landscape architects to help design the new City Park in San Diego. The Olmsted Brothers and John Nolen were later hired to assist with the design plans for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition. While the Olmsted Brothers eventually withdrew from working on this project due to opposing views of landscape preservation, Nolen remained as parks were becoming more urbanized during the City Beautiful movement. [4]

City Park changed to Balboa Park, and the original pastoral vision of secluded nature was fading. The City Beautiful movement focused on beautifying the city by incorporating more trees, bringing nature to people in the city, and upgrading buildings to create a nicer place for locals and visitors. A form of this movement focussed on bringing the city into nature, and incorporating more buildings or structures in parks. Balboa Park has continued to evolve as a form of the City Beautiful with the incorporation of museums, tennis courts, a zoo, and other buildings in the park.

1920 Balboa Park Botanical Gardens Fountains

There are still remnants of the early designer’s vision of nature in the park, like the lining of eucalyptus and palms along the roadways and outskirts of the park. The goal of the trees outlining the park was to create a secluded nature escape in the park. Early park planners saw it as a need for people to connect with nature away from the city life. In the twenty-first century of digital connectivity, there is a greater need for people to connect back to nature as advocated by these early park planners. Balboa Park is a place that offers opportunities for people to connect to nature in areas of the park, and by participating in events such as Arbor Day and Earth Day in the park.

Citations:

-

Carter, Nancy Carol. “Mary B. Coulston: Unsung Planner of Balboa Park.” Journal of San DiegoHistory 58, no. 3 (Summer 2012): 177-202.

-

Macchio, Melanie. “John Nolen and San Diego’s Early Residential Planning in the Mission Hills Area.” The Journal of San Diego.

- Marston, Mary Gilman. George White Marston: A Family Chronicle. Los Angeles: The Ward Ritchie Press, 1956. Hathi Trust https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31822008190787&view=1up&seq=21.

-

MacPhail, Elizabeth C. Kate Sessions Pioneer Horticulturist. San Diego: San Diego Historical Society, 1976.

- San Diego History Center. “George White Marston (1850-1946).” San Diego History Center. https://sandiegohistory.org/archives/biographysubject/gwmarston/.

-

Stevenson, Elizabeth. A Life of Frederick Law Olmsted: Park Maker With a New Introduction by the Author. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2000.