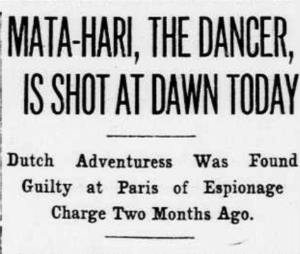

Figure 1.

In the dataset, Mata Hari was scarcely mentioned in U.S. newspapers before her arrest in 1917. Mata Hari only appears in American newspaper articles a few times from 1905, the start of her dancing career, and 1916, the near end of her career. It is evident that Mata Hari was heavily reported on following the shocking news of her arrest and most significantly her execution in 1917. Mata Hari’s death occurred six months after the U.S. intervention of World War I, the emphasized reportage on the dancer spy is visually high. Thus, she was propelled into the American conscious from 1917 to 1918.

From this conclusion in the data, I propose interpretations of her immersion into the U.S. perception of gender and war. Her depiction was pitted against the desired expression of femininity during war in the national crusade against the threat of corrupt women and venereal disease. Her debut in the media brought portrayals that exhibit the gendered patriotism, gendered national identity, and constructed definition of femininity during World War I. She was an alleged German Spy perceived to be justly murdered. Her death in the media served as a morale boost and scapegoat for Ally casualties among the masses. Not only was she a tangible common enemy, she proved to be an efficient figurehead to blame and invoke revenge among the American public. This helped to unify the U.S. to support the war effort. Issues of American Nationalism amid the immigrant threats placed Mata Hari’s “Oriental” identity at an emphasis for her justified demise which showcase the racial and cultural prejudices. Once a vilified female, she evolved to a celebrated liberated woman in popular culture, reflecting the change in commonly supported notions of femininity in the 1920s.

She trended similarly during the early and late 1920s, showing an increase as the tensions between countries and the beginning of the Great Depression. Mata Hari can be seen as a figure in history and popular culture whose portrayals are malleable to invoke and/or express attitudes of various political, economical, social, and cultural events and changes.

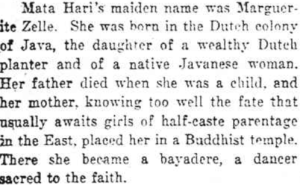

Figure 2.

This figure can be seen to follow the trend of Mata Hari in U.S. newspapers from 1917 to 1929. In 1917, newspaper articles explicitly tied Mata Hari to “Oriental” origins and culture, most newspaper articles reported her to be both Dutch and Javanese/ Japanese/ Indian/ and “Oriental.” The depictions of Mata Hari as an “Oriental” created notions of gendered and inferior views of the East in the U.S. based on her enemy status. Newspaper articles also focused heavily on Mata Hari as a German. This is another emphasis on the national and cultural superiority of America as her death was celebrated as an Ally victory.

The “Eastern” portrayals of Mata Hari also exhibit the popularity and construction of Orientalism in the United States amongst the media. The image of Mata Hari as a “Javanese” and “Oriental” mirrored the Asian exclusion and anti-Asian views, that were evident in American legislation such as the Immigration Act of 1917. Anxieties and fears of adversaries in their midst during World War I triggered oppositions of immigrants and those who were not “fully American.” Fears of espionage by these immigrants and first-generation Americans resulted in discrimination. As well as strong feelings of American ethnocentrism and public displays of patriotism. The media’s representation and reportage on Mata Hari portrayed her as a palpable extension of the German and Asian enemies. Mata Hari’s portrayal exhibited the American viewpoint of its masculine superiority compared to Southeast Asian inferiority and feminine nature.

Throughout the 1920s, such viewpoints and attitudes were continued through the popularization of Eugenics and economic imperialistic tendencies of the U.S. The Immigration Act of 1924 expanded on the 1917 act, furthering the gap between natives and immigrants. Western economic and colonial interests influenced the constructed interpretations of Indonesia and other Asian countries Mata Hari was connected to. As racial prejudices legitimized anti-immigrant legislation, Mata Hari’s connections with Asia and indigenous religions of the East served to further propagate Orientalist stereotypes. This constructed Orientalism further skewed Americans’ stereotypes of non-Western cultures and ideologies to justify American interventions in Southeast Asia.

For the years with no newspaper articles, there were a few newspapers in the LOC database between 1923 to 1925.Out of the five articles, none specifically connect Mata Hari to being “Oriental”, therefore there are gaps in the data for those years.

* All data is sourced from the Library of Congress Chronicling America online newspaper database and can be found on the methodology page of the website. The dataset does not incorporate all U.S. newspaper articles but still encompass a large and diverse sample of American media from multiple cities and states.